Wednesday, December 30, 2015

2015 in review: pan and the big short

Pan: (dir: Joe Wright) Pan is pure, breathless, grand spectacle, colorful and quick-moving, visually inventive, sometimes ingenious. The use of "Smells Like Teen Spirit" and "Blitzkrieg Bop" is inspired and powerful. Hugh Jackman as the pirate is absolutely marvellous. And still it manages to leave one entirely emotionally unengaged.

As in so much non-thinking children's fare, the bulk of the adult characters are cartoonishly evil, a few are angelically good (which means they exist for the sole purpose of loving, nurturing and furthering the boy-child at the film's center), and there is one weak but well-meaning clown-figure to mediate between the two groups. The mermaids, who might be so interestingly dangerous, are instead a boy's wet-dream, identical twin supermodels. The moral platitudes the film winds up promoting are ancient, etiolated (and, arguably, patently false) chestnuts like "a mother's love is perfect and stretches beyond time, space, even death" and "believe in yourself, and you can do anything!" These themes often find themselves attached to Peter Pan projects, but a return to the original book reveals a subtle darkness, and a cynical humor underlying themes of both motherhood and achievement. Wouldn't it be nice to explore some of that?

IN SUMMARY: Turn off your brain and enjoy the prettiness. Or just watch something else.

the Big Short: (dir: Adam McKay) It seems impossible that this story, mostly concerned with communicating the intricacies of banking minutiae, is told in an entertaining fashion, but it really is. Avoiding the linear and conventional, McKay keeps the pace jumping by having his characters break the fourth wall on occasion, usually to assure us either that a thing didn't really happen like they're showing it, or that yes, it really DID happen like this, and by bringing in celebrities (Anthony Bourdain, Selena Gomez, some naked chick in a bubble-bath whose name I didn't recognize) to tell stories illustrating the twistier expositionary points.

It's not Christian Bale's best work. Steve Carrell's character, depressed and growing increasingly so throughout, seems to be the only one facing the insanity of the situation with a sane reaction. You expect him at every moment to go off the roof.

IN SUMMARY: It's about the build-up to the crash, for Chrissake. As fun as they make it, it's still depressing as hell. Here's the thing: these guys, these underdogs, are betting on the world economy crashing, and we want them to win, and the slimy bankers to lose. But then when they do win, it means the fucking world economy has crashed. As the Brad Pitt character says (I'm paraphrasing), "You won. Just don't dance about it." In the lobby on the way out, I told my boyfriend I wanted to cancel my retirement fund. (I haven't.) In that moment, it felt like poison to the soul, having even the slightest contact with that world of hideous grotesquerie.

Saturday, December 26, 2015

2015 in review: before we go

*SPOILER ALERT*

(dir: Chris Evans) Everyone knows you can make the switch from one side of the camera to the other. Dick Powell did it, after two decades of the mad fuckery that is the life of a matinee idol. He directed five pictures in all, including the atomic-age melodrama Split Second, the infamous the Conqueror, in which the Duke armors up as Genghis Khan, a couple of Mitchum-powered war pictures and a remake of It Happened One Night starring his wife, June Allyson. Then there's Charles Laughton, who hit it out of the park on the first swing with Night of the Hunter, a piece of brilliance so bold and visionary that nobody was ready for it; his masterstroke went unheeded; everyone turned their heads politely and chuckled in vague embarrassment, and he never directed another. Some would call that a shame; I call it a damn tragedy. Costner, Streisand, Gibson, Eastwood all made the jump and landed in one piece, winning accolades and ready acceptance. Some have even worked their way up to sit among the highest of the adepts: Eastwood with Unforgiven and, I would argue, Gibson with Apocalypto.

I'm willing to concede that two of the big strikes against Before We Go, the title (cashing in on the Linklater/Delpy/Hawke trilogy) and Evans himself playing the lead, were probably enforced from without by the money-men. You can hear the meeting, right? "So these kids meet cute, they wander around all night, it's like that Ethan Hawke picture, am I right? People will think it's another one in the series if we stick a 'before' in there. And don't think you're not starring in this, pal. These girls, they don't give a crap what you do behind the camera, as long as that pretty mug is in front of it." (Don't you hope producers really talk this way, like they're in a bad '30s movie? Like Bruce Campbell in the Hudsucker Proxy? "Say, what gives?")

I hope Evans sticks with it. Learning your craft in public is tough, probably tougher when you're one of the most famous handsome men currently extant in the galaxy. (Although it'd be a thousand times tougher if he were a woman, yeah.) The good news is, he's not travelling down the Charles Laughton road. But that's also the bad news, you know? In forty years, nobody's going to dig this up and call it a forgotten treasure.

The plot summary my cigar-chomping producer guy gave is correct: girl meets boy, she's had her purse snatched and he's playing trumpet in the train station. They walk around all night, falling just a little bit in love, and part in the morning, after two chaste kisses, to return to their respective lives, forever changed by the brief encounter. As formulas go, it's not a sure bet, but it's no longshot; we all know you can make it work, and on a slim budget, to boot.

This one suffers from a weak script, leads who share what you might call a friendship-chemistry but no fire, and a main actor who, like John Wayne when he finally found Howard Hawks, needs an objective director to remind him to stop depending so much on his eyebrows.

Alice Eve, so winsome and charming in Men in Black III, and, as I recall, fully satisfactory in Star Trek Into Darkness (although that whole film seems to have folded into a mental black hole from which my memory can access only a few unextraordinary glimpses), leaves the fun behind for this one, coming across stodgily, unremarkably. I am ready to give her the benefit of the doubt and place the blame elsewhere, perhaps at the writer's doorstep. For instance, it's unclear from the start why this handsome busker latches so firmly and immediately onto this rude, icy woman of a Type That Is Not His (he says it later on, straight out, "You're not my type"), but that kind of "don't ask" is typical of this script.

Here, look, here's her story: she's been married for several years, and for the last few she's been secretly reading her husband's intimate emails to his clandestine lover, but never let on. The marriage went on as before, he never guessed she knew, and the only difference was that she recognized it all as one vast sham.

This is HIS story: for six years he's been carrying a torch for his undergrad romance, the girlfriend who broke his heart and got away. They've had no contact at all during this time, but he's thought of her every day, dreamt over and over of her return into his arms, into his life. This is a fellow we're supposed to buy as healthy, strong, creative, a talented jazzman, a guy with Chris Evans' looks, mind you, and well-to-do enough to carry eighty bucks folding money in his pocket while he busks.

Something's wrong with both these pictures, you see what I mean? This cat either has a drug habit that's inhibiting him from emotional maturity, or he's got some kind of compulsive disorder. This woman, I'm sorry, I don't buy it. You don't keep reading the emails for that long without the habit itself bringing a change into the marriage: either it's going to break, she's going to fold, he's going to realize she knows, SOME damn thing. My point is these are not stories from the real world. These are fantasy, made-up stories. They could be reasonably delivered by a Billy Liar or a Walter Mitty, or someone whose life is on hold due to drugs or neurosis or the shyness that comes from extreme homeliness or from having ducked out of life to care for your ailing mother, like in the Haunting of Hill House. But healthy, grown-up people with money to spend on artwork and haircuts, like these are supposed to be? I don't buy it, sorry, not for a nickel.

I'll tell you the one thing I DO like about this story, the one thing I've never seen before and worked like gangbusters: the ex-girlfriend is not a bitch, and she and the trumpet-playing torch-bearer still have a good, strong chemistry. The relationship didn't work because they met at the wrong time, that's all, and now there's too much water under the bridge, it's still the wrong time. You never see that in film, but it happens all the time in life. That was a great choice on Evans' part, to shoot the reunion as if it were a love scene, with gazes locking across a crowded room, melty-eyed smiles, pounding hearts, the whole nine yards.

As far as the camerawork goes, they say that nascent directors choose handheld because handheld is easier to cut. Alright, I'll allow it, this one time. But as soon as you learn your craft, you buy a damn tripod, do I make myself clear? Handheld works OK for this kind of film, but don't you dare make it your automatic, unthinking, fallback choice. Find yourself a crackerjack editor instead, and get to work on your Scorsese/Schoonmaker, Tarantino/Menke relationship.

IN SUMMARY: I can't think of a compelling reason to watch it unless you're an Evans completist. The upside is that he's been in far worse films, and it's not, indeed, the worst romance ever made. The downside is that I can't think of a compelling reason to watch it, unless you're an Evans completist.

Friday, December 25, 2015

2015 in review: lambert and stamp

(dir: James D Cooper) A fascinating subject for a documentary, illuminating a pair of men as influential in the rock 'n' roll era as Brian Epstein or Andrew Loog Oldham. These are the colorful figures behind the rise and super-empire of The Who.

The tricky bit with docs, though, is that they rise and fall on the quality of the interviews. Lambert is dead (and, though it's hinted the death was shadowy and probably drug-related, they never do tell us how or when), and Stamp is the sort of talker who skims across the tops of things, going sidetracked into vocal fillers (long chains made of "you know"s and "um"s) and off-shoots, using a lot of space to say frustratingly little. He needed a more disciplined interviewer; he definitely needed a more determined editor.

Another reason docs fail to rise up into greatness is because they're made when too many of the folks are still alive, and so everyone is treading carefully to avoid stepping on toes, a dynamic fully in play here. Toes were already well-smashed in olden times, one can sense, and we can see Daltrey in particular trying terribly hard to avoid hurting Stamp's feelings, and to avoid pissing Townshend off, as well, which speaks well of Daltrey as a human, but it makes for very weak copy. All those moments when we watch a dark piece of truth pass unheralded behind his eyes, a piece which he chooses not to speak... those are the very words we long to hear. Townshend comes across as a man who is choosing his words carefully not so much to misdirect his interviewer as to avoid looking too closely at something himself, some old truth or possibly a mendacious aspect of his own personal myth.

In any case, it's useful to know going in that this is not at all a history of The Who; you really need to have taken your Who 101 before you watch it to have the basics readily to hand. Probably a simple viewing of the Kids Are Alright, one of the best rock docs ever made, will suffice. And it won't hurt to have a working background in Carnaby Street history, to boot: for this, I heartily recommend (Timbers fan) Shawn Levy's brilliant Ready, Steady, Go!, a wonderful book.

IN SUMMARY: I'm very glad this film was made, because now this footage can be used again once all the main players are dead and buried, when it's time for the REAL story to come out. This is an exercise in the wrapping up of loose ends for the kids involved. In other words, it's not really for us, it's for them, particularly for Stamp, and possibly for Daltrey, an opportunity for him to make peace with his past, or at least to bury some demons a bit more deeply. And although I'm glad to see that the kids are alright, I'm still wishing for a deeper digging into the Carnaby Street doings of these two probably once-nefarious characters.

Wednesday, December 23, 2015

2015 in review: spectre

(dir: Sam Mendes) Daniel Craig is the sexiest Bond, no question. He qualifies for that just from the way he looks at Moneypenny (Naomie Harris) when he's charming her into doing something against her better judgment. In fact, he has a way of looking at a woman as if she's the most beautiful he's ever seen, and it's marvellously seductive.

He's also the most intelligent Bond, so when he claims, as he does in this one, a tendency toward unthinking action, it's difficult to swallow it as gospel. We can SEE him introspecting, see it in a way that never would have occurred to Connery or Moore or Brosnan. But Craig gets a pass from the writers, too: he is allowed a dignity that previous Bonds were not. For instance, in the first scene, a Day-of-the-Dead sequence (very impressive, but would not have suffered from some chopping down), Bond slips out of a beauty's hotel room window, promising he won't be gone long. He blows up a building, has a big fight in a helicopter, the usual stuff. But if this were the Pierce Brosnan version, the writers would make him land the copter on the hotel roof and walk back into the girl's room brushing dust off his lapel and saying, "Now, where were we?" Craig never has to do that kind of dirty work, the leering stuff, and good riddance to it.

Still, these movies, the Craig Bonds, have lost something in the gaining of the substance. They're not candy anymore; they're no longer easy to watch, not always even fun. Every time they go back to London, for a start, it's like being sucked into an Orwellian dystopia from which hope and sunlight have been forever exiled. Any escape, even to the desert stronghold of a dastardly foe, seems a relief. And because Bond is fully human now, he has something to lose besides his sex-parts or his life. There is a Mephistophelean moment at the end when the villain (Christoph Waltz) tempts 007 to give up his soul in exchange for one moment of violent satisfaction, and, for a second, I really believed he might.

IN SUMMARY: over-earnest, overlong and pompous. What saves it are the likeable performances (Craig, Waltz, Harris, Lea Seydoux, Ben Whishaw. Ralph Fiennes is bravely commonplace as the deceased M's replacement, a terribly efficient clerk who's risen gradually to a post of importance).

And remember when you could count on a Bond opening credit sequence to be hypnotic, even if you didn't like the movie itself? No longer. The one is overblown, awkward, and the theme song sucks.

Tuesday, December 15, 2015

halloweenfest evening twelve: spring, kaidan, and thale

Spring: (2014. dir: Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead) Kind of a pretty love story set in the shadow of Vesuvius, and probably the less you know going in, the better. But yes, there is a monster, and yes, a couple of bloody deaths.

*SPOILER ALERT*: Remember the original Stargate? Before all the TV spinoffs, the old Roland Emmerich movie with Spader and Kurt Russell? Remember when they encounter Ra, the supreme being, the entity as old as time, and you think to yourself, "That's it? Old as the aeons, and all you are is a mincing fashion-plate?" This is not quite that bad, but the millennia-old critter is still nowhere near as wonderful as Jarmusch's nosferatu in Only Lovers Left Alive. Maybe just watch that instead. Or at least make sure you watch that one as well. It's so seldom that Jarmusch does something marvellous, it's only fair to celebrate it when he does.

Kaidan: (2007. dir: Hideo Nakata) A gorgeous ghost story set in feudal Japan. At its center, geographically, lies a haunted pool; teleologically, the center is a House-of-Atreus curse on two families, uniting them karmically. The inciting event is given in diegetic prologue: a money-lender demands repayment of his debt from a samurai, who kills him and dumps his body in the (already haunted) pool. Both men are sinners; one is a usurer, the other a murderer. The tendrils of bloody consequence will wind through three generations and sidelong to affect cousins as well. In the end, there is a sense, with its strikingly eerie last image, that the curse may be played out, but perhaps only because the last survivor, the watching sister, has no children.

Movies in Japanese, more than other languages, frustrate because I often suspect the subtitles are not telling the whole story, that I'm missing out on the subtleties, and this is no exception. Some of the phraseology is modern, as well ("suck it up", "ask you out"), jarring one into a place of uncomfortable anachronism.

Still, the photography, the strangeness of the story, the sense of doom, the beauty of the palette, all together weave a concerted spell.

Thale: (2012. dir: Aleksander L. Nordaas) A lovable duo of crime-scene cleaners stumbles upon Huldra, a being from Norwegian mythology, stuck in a mouldering basement. The acting is lovely, the script communicates itself well even across the language barrier, and the creature herself is a beguiling mix of innocence and monstrosity. The story maintains a wistful melancholy travelling through a convincingly otherworldly atmosphere.

Tuesday, December 8, 2015

halloweenfest evening eleven: the legacy, the editor, the nightmare, the final girls

the Legacy: (1978. dir: Richard Marquand) Katharine Ross and Sam Elliot are so young and beautiful, and they seem to take such pleasure in one another's company that this slow-paced, clumsily-plotted horror classic is hard to resist. I've never seen Ross look so happy and relaxed, and this may be the only horror film in which the hero sells her soul to Satan and comes up with a happy ending and enhanced personal relationships.

Let me add a word about Margaret Tyzack (who plays the... well, the witch's familiar, with a nurse's costume and nine lives): she's part of that generation of English actresses who seem entirely practical, strong, and so layered with complexity that every movement of the eye seems to communicate something definite but mysterious, as if she knows something that we, in our simplicity, never will entirely understand. She reminds me in this of the magnificent Billie Whitelaw in the Omen, and was there ever a stronger and more unsettling presence onscreen than that one?

the Editor: (2014. dir: Matthew Kennedy & Adam Brooks) A loving send-up of Italian Giallos from the '70s, done with attention to detail: conspicuously bad dubbing, sudden zooms into close-up, swimming fades into flashback, sexually punning prop placement. Laughable amounts of completely gratuitous nudity and violent machismo, buckets of gore, bountiful moustaches, ridiculous plot-turns. Like most send-ups, the joke gets old before the end, but it has its enjoyable moments. My favorite line is when the investigating policeman (a detective named Porphyry) is told by a priest that in ancient times, editors were mistrusted as "bridges to the nether-regions."

the Nightmare: (2015. dir: Rodney Ascher) Ascher continues his journey as the most inventive of documentarians with this terrifying follow-up to 2012's Room 237. The Nightmare explores an age-old Fortean manifestation sometimes called The Old Hag (see here and here). It's a sleep disturbance as old as mythology, and shows up in the horror-lore of most every culture around the world. You wake up; you can't move; something awful approaches the bed, and you are helpless to do anything about it.

Ascher doesn't involve the rationalists. He goes straight to the sufferers, and has them tell their stories, some of which are re-enacted. Some involved have conquered or at least tamed the ongoing horror; others have resigned themselves to continued suffering, and, as one man says, eventual death within its throes. Some remember suffering it from infancy; one, chillingly, claims to have "caught" it from a girlfriend who told him the story of her sleep paralysis episodes, and to have passed it on to another girl the same way.

the Final Girls: (2015. dir: Todd Strauss-Schulson) At last! After several decades of movies about the angstiness of father-son relationships, here's an inventive, funny, and touching look at a girl coming to terms with her mother's untimely demise, all dolled up in the robes of a loving homage to slasher films. Truly, it's like no other movie I've seen, and I mean that in the best way.

When the Masked Killer leaps, ablaze, from a second story window, it is awesome to behold. When the characters transition into black-and-white "flashback" mode, or find themselves caught in slow-motion, it's done in playful and engaging ways. The comedy feels light-hearted and improvised, and the "slut" girl's strip-tease after she's taken too much Adderall (to the buttrock classic "Cherry Pie" by '80s hair-farmers Warrant) is one for the ages.

Wednesday, December 2, 2015

halloweenfest double feature: the traveler and sundown

the Traveler: (2010. dir: Michael Oblowitz) High Plains Drifter played out on the set of Assault on Precinct 13, only High Plains Drifter was written all right and this was written all wrong. In this one, we see the guilt-scene, repeatedly, in detail; we know everyone's secret almost from the beginning. There's nothing, -- OK, some, but not much, -- to be revealed. All we have are the vengeance-killings to watch, one after the other, and five million other movies give us that much. At the end of High Plains Drifter, there still lingers an exhalation of enigma. This one makes even the full-blown supernatural feel solid, humdrum, everyday.

Mr. Nobody (Val Kilmer) walks into a cop-shop on Christmas Eve to confess to killings he hasn't yet committed. The good parts are in the details, like the peeling green paint and buzzing fluorescent lights. A piece of Mozart's "Lachrymosa" runs an eerie thread throughout, coloring the movie much as the faux-"Deguello" did Rio Bravo. There's a nice fairy-tale tag at the end in which the supernatural bad guy gets put down by the power of his name spoken aloud, but it's tacked on in an awkward way and doesn't really fit. The pieces don't jive; the world does not cohere.

Kilmer continues his slow and steady transmogrification into Brando, and I mean that in a good way. Even in soporific mode, he draws the eye, and he's still got some mischief in him.

Sundown: the Vampire in Retreat (1989. dir: Anthony Hickox) An embarrassingly misguided attempt at a broad-stroked, horror/western/humor gallimaufry, the "humor" more along the lines of Monster Squad than Evil Dead, but not even achieving success at that humble level. Even Bruce Campbell and his near-ridiculous facility with this kind of thing takes a swing and a miss in the bumbling Van Helsing role. And it's a home-run swing, too, so he misses hard. Like when a soccer forward goes down onto his back for a bicycle-kick: if the ball hits the net, people use words like "sublime" and "miraculous", but even if you're Lionel Messi, you look pretty stupid when you miss. In this movie, everyone misses. Only Deborah Foreman (from Valley Girl) emerges with any dignity intact, albeit just barely, which makes me think I ought to revisit her work.

Here's the idea: Count Mardulak (David Carradine) has established, with the help of extreme sunblock and synthetic blood, a colony of reformed vampires in a remote part of the desert. There are problems when the occasional human stumbles in, and more problems when the old-school vamps posse up with guns shooting wooden bullets and vow to wipe out the apostasy. Nothing is funny, and Carradine knows it, giving so vacant a performance as to seem in retrospect almost transparent. The only part that's any fun is the end-scene when the humans erect a cross atop the mansion and the unrepentant vampires start exploding into flame, but that's just a nice special effect. This, however, is followed hard upon by an interesting theosophical moment when Mardulak, teary-eyed, realizes that his followers are intact because the Christian God has, at last, "forgiven" them. Has there ever been a movie in which the repentant vampire actively seeks forgiveness from a God in which he believes? Because I'd like to watch that movie.

But it has to be better than this one.

Wednesday, November 25, 2015

halloweenfest triple feature: monsters, absentia, neverlake

Monsters: (2010. dir: Gareth Edwards) Gorgeous movie about two travellers falling in love at the end of the world. It can be read as an allegory concerning U.S.-Mexico border relations, with a melancholy undermessage about how our fear-inspired bellicosities lead to our downfall, but that's mere reduction, and it's far vaster than that. They say it was done on a limited budget, but that's hard to see. The world Edwards has created, with its gas masks, light-being infested jungles, coyotes overcharging for "evacuations", and its alien-invaded "infected zone", feels entirely and fully realized. Really something extraordinary.

Absentia: (2011. dir: Mike Flanagan) Ultra low-budget but inventive and well-executed chiller about two sisters and the horror-film equivalent of the troll who lives beneath the bridge and drags travellers to their doom. Strong, realistic women, an otherworldly threat that is mostly suggested and still effective, and handheld photography that looks clean and doesn't distract from the story. It's a movie made of quiet suggestion, its mystery full-blown but never, as is usual in life, witnessed in its entirety by any single person. Its most unsettling lines are quietly delivered ("You traded with it. I wish you hadn't. It fixates.") and its best exposition given entirely through succinct visuals.

*SPOILER ALERT*

Neverlake: (2013. dir: Riccardo Paoletti) Not straight-out horror, but what you might call Young Adult Horror-Ish. A teenaged girl raised by a grandmother in America is called back to visit her long-estranged father at his villa in Tuscany. Thematically, it fits in with Jessabelle, in that the children (both dead and alive) suffer by and are called upon to rectify the sins of the father. It also falls in with a fairly new and burgeoning tendency toward the examination of the daughter's search for the mother, a new yearning toward the (at this point, still wounded) matriarchal, as witnessed in the Final Girls and the Falling.

The editing and photography far outshine the script here, as does the story itself, which involves a lake into which ancient Etruscans chucked images in order to invoke its healing properties. Toss into the mix a doctor/father who seems to have stepped, ethically, anyway, out of Eyes Without a Face, and there's a very dark story to be told. The fatal weakness of it lies in the dialogue, which hits the ear as if conjured clunkily from the pages of a Young Adult novel, and a pacing which belongs more to the Twilight-esque "don't worry, everything will turn out alright" template than to bona fide horror. In effect, Paoletti wants to tell you his very dark story without taking the risk of scaring you at all.

Monday, November 16, 2015

halloweenfest evening eight: three to avoid

the Thing Below: (2004. dir: Jim Wynorski) Co-opting the plot of Alien and moving it to the middle of the ocean, the Thing Below gives us a ship sent by evil government officials to drag some unknown critter up out of the depths and transport the cargo home. They meet with some weather, the glass jar it's trapped in breaks, yada yada. If you've seen a Wynorski film, you know what to expect. Midway in, Glori-Anne Gilbert appears out of nowhere to do a completely gratuitous, five-minute strip-tease. (I love Glori-Anne Gilbert! You'll remember her from the completely gratuitous skinnydipping scene in Wynorski's equally bad Curse of the Komodo.)

In fact, the striptease is probably the best reason to watch it.

Borgman: (2013. dir: Alex van Warmerdam) Annoying Dutch movie in which quirky transients (possibly the devil and his cohorts) teach some rich folks a lesson by murdering them and their servants, then leading their children away to an unspecified fate. The women in question (the matriarch, the nanny) are ridiculously easy to seduce and obsessive once seduced. Yeah, you're going to tell me it's an allegory, right? That I'm not looking at it in the proper light. That in the original language, it's funny!

Whatever. The only really cool thing is the dogs.

Unholy: (2007. dir: Daryl Goldberg) Adrienne Barbeau swept up in occult governmental research into invisibility, time travel, and mind control? It could be interesting, right? Alas, not really. They never delve much further into these issues beyond the naming of them ("the Unholy Trinity", they're called. Spooky!). There's no true twistiness (alright, there's one good twist, but it's not sufficiently satisfying to absolve the bulk of the crapfest), no images so dark and true they gnaw into your underconscious. There's a conspiracy (who's part of it? everyone? you DON'T SAY!), a bestial Nazi behind the whole thing (yawn), and no interesting theories or ideas come forward. No decent dialogue, either, for that matter.

And who doesn't love Adrienne Barbeau? She deserves better than this.

Thursday, November 12, 2015

halloweenfest evening seven: jessabelle and hands of the ripper

*SPOILER ALERT*

Jessabelle: (2014. dir: Kevin Greutert) Seeking to employ a creeping tension rather than out-and-out scares (and, honestly, the tension never stretches all the way taut), Jessabelle works best in its atmosphere (hoodoo-infused Louisiana bayous) and effective story-telling.

After her life is derailed by an accident, Jessie (Sarah Snook from Predestination) is forced back to her hometown and into her estranged father's crumbling old Southern Gothic house. Immediately haunted by nightmares and spooked by old tarot-reading videotapes left by her dead mother (Joelle Carter, Ava Crowder from Justified, wonderful), she begins, wheelchair-bound but helped along by a childhood sweetheart (Mark Webber), to try and unravel the decaying family secrets.

It's got plot-holes, but they're not fatal: she claims she hasn't seen her father since she was a baby, but when he brings her back to his old family home, he is still living in the tiny backwater where she was raised by her aunt; also, a sudden, unplanned, "secret" adoption staying secret in so small a bayou community is tough to swallow. The visual tropes the haint employs are satisfyingly organic to its plight: the recurring creep of black sludge mirrors the emptying of the underwater coffin, for instance. It's got echoes of that other voodoo-bayou classic, the Skeleton Key, but allows for at least a little feeling of redemption in the end. Although it feels shockingly anathema to our modern sense of fair play, the sins of the father visited upon the child, this kind of vengeance enjoys a long and ongoing tradition in certain circles, and the racial hatred at the heart of the original crime lends an air of the righteous to the avenging furies.

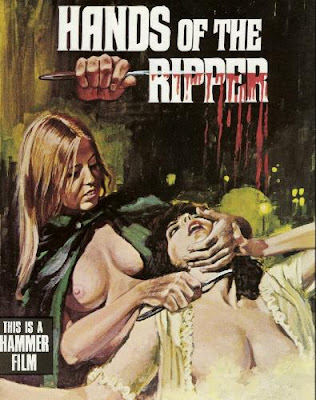

Hands of the Ripper: (1971. dir: Peter Sasdy) Don't be fooled by the poster. This Hammer film, although not without its merit, is far too prim to be emblematized by such Italianate spudoratezza.

A little girl watches Jack the Ripper (who is her father) murder her mother, then he kisses his daughter before he vanishes. Fast forward several years. The orphaned teenager, Anna (Angharad Rees) is being raised (badly) by a fake medium, who uses her to falsify the voices of dead children during her seances. Murderous impulses can apparently be passed down through the DNA, though, because once puberty kicks in, she finds herself falling into deadly fugue states triggered by a combination of flickering lights and kisses.

A well-meaning Freudian (Eric Porter) takes her into his home to try and understand the mechanisms of the homocidal mind. Incredibly, he sticks by her although she commits five or six murders, some in his very house, within the course of two or three days. (It's an interesting Freudian side-issue that so many Victorians of either gender feel compelled to kiss her on so short an acquaintance.)

There's not much more to it than that. There are some nice visuals, as in the climactic scene in St. Paul's, and Jane Merrow brings the needed innocence and light as the sweet, blind fiancee of the doctor's son.

Sunday, November 8, 2015

halloweenfest evening six: trouble at the girls' school

the Falling: (2014. dir: Carol Morley) Inspired by a Fortean phenomenon known as "falling sickness", a hysterical contagion traditionally rising up in girls' schools or convents (see here) this movie has self-conscious pretentions towards Picnic at Hanging Rock. It fails in that direction because it cannot leave its mystery alone, but must turn over every rock, literalize and spell out the urge behind every nuance. Similarly, Maisie Williams' acting style, which can be refreshingly simple and candid in Game of Thrones, is altogether too literal to carry this off, a role which demands subtlety, demands secrets.

Still, a wonderful thing happened about halfway into this film: I realized that I was being shown the story almost exclusively from the feminine point of view. Men, all men, are entirely sidelined here, their opinions and feelings almost wholely discounted as unimportant. It's a wonderful relief, allowing a feeling of exploration, of charting unknown territory. The women are downtrodden, yes, sometimes neurotic, trapped by the actions and opinions of men, but it is only women's reactions to their own hardships which are of interest to this film-maker, and it is a revelatory experience. The sole exception is when she lets us into the brother's head for a piece, and it's a mistake. She does it (I assume) because she thinks it will help make palatable a particularly delicate and pivotal plot-turn if we know that he was enchanted by the doomed girl, that she wasn't just another conquest for him. It doesn't, and it was a mistake to try. I mean, the plot-turn might have been made palatable, but she didn't accomplish it, and some level of purity the film might have had without the boy's intrusion is diluted. In the end, it all seems a bit contrived.

*SPOILER ALERT*

the Moth Diaries: (2011. dir: Mary Harron) If the Falling failed because it was too literal, this one fails because it wants to have its metaphysical cake and still call it psychological. Are the strange goings-on manifestations of a teenaged girl's journey from the darkness of her father's suicide into redemption? Or is there indeed a vampire amongst the budding pubescents?

The director of American Psycho stays perhaps too true to the novel this time. Any power wielded by a first-person narration on the page is often lost once it's imprisoned in flickering light, and the transition doesn't work here. If this is the story of a girl's psychic journey through madness into new life, then why are people dying? Is that all in her head? If people really are dying, then who's killing them? Rebecca herself? The vampire/ghost girl who so eerily mirrors her in circumstance and obsessive nature? In the denouement, when we are given to believe it's all just been a chrysalis stage leading up to Rebecca's fiery release from the bondage of her childhood torment, it feels embarrassingly simplistic. Two deaths, an expulsion, and a terrible fire, all to further one girl's psychological healing? If it worked in the Young Adult novel, it must have been because print allows for an ambiguity which only the best film-makers (like Peter Weir) can conjure, and Harron doesn't come near to making this work.

halloweenfest evening five: dead awake

*SPOILER ALERT*

(2010. dir: Omar Naim) Mangled attempt at a "night-sea journey" movie (Siesta, Jacob's Ladder, the Machinist) so useless that it never even pushes off-shore, just keeps chasing its own tail in the tide-pools, filling time until the contrived sap of its ending.

Dylan (Nick Stahl) works at a funeral parlor in his hometown, having given up on life when his parents were killed in an accident and when, in his grief, he lost his soul-mate (Amy Smart) to another man. He stages his own death (obituary, wake, even tombstone) in a wild attempt to glean whether anyone would care. Or is he really dead, and trapped in a purgatorial dimension? When an unknown woman shows up at his coffin-side, leading him into her dark world, everything turns weird and hallucinatory.

Only not enough so. A true success in this genre melds reality and hallucination so seamlessly that you eventually stop trying to sort them and relax into the march of the story toward the ineluctable, melancholy release which ends it. The ending should feel like a destiny, meted out gently by demiurgic Fates. The motives and conditioning forces buffeting the beleaguered lead should be compelling enough (unacknowledged death, extreme guilt) to warrant the living nightmare. A second viewing should reinforce that the writer knew from the beginning which characters belong to which world: actual, hallucinated, or something in between.

This one makes a mess of it, then throws in the towel completely and stops pretending to be other than hogwash with its forced happy ending. To give the writer his due, it feels like The Evil Studio intervened at the last minute, and that the original, more interesting ending (that his Irish friends are in fact his dead parents) got tossed. The Rose McGowan character, a tweaker with a debt to pay, is even more problematic, and her story doesn't hold up under the barest scrutiny. How could she steal the ring and pawn it under the circumstances? Only if the whole "underworld" she shows him is an "otherworld", pawn shop and mob thugs included, and solid items, like a ring, can traverse the walls between them. Which would have been a more interesting road to travel, right? But someone, possible The Evil Studio, didn't have the grit to follow it through.

I feel bad for Nick Stahl. He deserves better than this.

Sunday, November 1, 2015

halloweenfest evening four: you're next and dark fields

You're Next: (2011. dir: Adam Wingard) Wow. Worst family reunion EVER.

I don't like home invasion films. But, if you have to watch one, if you're inured to the ultraviolence they inevitably afford, this one has some greatness on offer. The best Final Girl ever, for one thing (Sharni Vinson), and there are perfect touches, like the pop CD stuck on endless repeat, those stoical animal masks, and some utterly shameless humor ("You never want to do anything interesting." "I think that's an unfair assessment." "Then fuck me on the bed next to your dead mother.").

The story was written with some care, although some early decisions the characters make are questionable, but isn't that part of the charm of the genre? (Like in the Geico ad: "Let's hide behind the wall of chainsaws!") And, by the end, the kills are far gone into the realm of absurdity. (It's worth it to hear a character ask where his brother is and get the reply, "I killed him with a blender.")

Adam Wingard, who would go on to give us the Guest (if you haven't seen it, for God's sake, man, go and do so) is already sure-handed and unwavering at the helm.

Dark Fields: (2009. dir: Douglas Schulze) There are these great things: Dee Wallace's eerily-swathed husband bearing her aloft in a green room. An enormous, tiled bathroom, like a chapel where the sacrament is performed. The marvellous faces of Cari's parents (Richard Lynch and Paula Ciccone). The top hat. The brightly-colored, shiny raincoats on the little girls. The strange voyage of Mr. Saul. Three separate and well-managed palettes for the three different time periods (1850s, 1950s, and present day). A Native American curse. A shaman bent on vengeance for the white man's genocide. And then, to render it all nearly useless, a script full of dreadful, clunky dialogue which does not come anywhere near to matching the beauty and grace and strangeness of the images.

If it were a silent film, or more nearly silent, say in the style of Valhalla Rising, it might have been magnificent. As it is, it's an undeniable failure, but with moments that will take your breath away.

Wednesday, October 28, 2015

halloweenfest evening three: ghosts of mars

(2001. dir: John Carpenter) OK. We've settled Mars. Mining camps, mostly. We've jerryrigged a certain amount of earth-like atmosphere and set up makeshift villages for the workers, established a running train. We also woke up something long dormant, a cloud of entities which travels like a thick red dust-storm and enters in through the ear, possessing the humans and turning them into Reavers. (If you're unclear as to what a Reaver is, watch Firefly episode three, "Bushwhacked".) The movie's Token Scientist, played by Joanna Cassidy (all the power-holders in this civilization of the future are women), along with the ranking officer (Natasha Henstridge, who has her own encounter with possession but beats it by taking drugs), together suss out that these are the ghosts of a long-dead, fish-faced, warrior race who are bent on genocidal destruction of any invading entity: in this case, the human race.

It's an unabashed Western, complete with posse, band of outlaws, an ambushed train, and a wrathful indigenous people being slaughtered for their land ("This is about one thing," says Henstridge's Lieutenant in her St. Crispin's Day speech. "Dominion. This is not their planet anymore.") Carpenter gets to play in some of his favorite sandboxes here: he takes the post-apocalyptic punk-chic of Escape from New York and ramps it up to full volume (a bra made out of severed human hands, anyone?) and restages Assault at Precinct 13 on the red planet, with cops and crooks teaming up to fight... well, ghosts. And, because these beings are incorporeal, and because once you kill the host they're going to find the next available ear to jump into, the killing doesn't make a whole lot of sense. Particularly once our band of heroes is safe on the train out of there and Henstridge's Lieutenant decides they need to STOP AND GO BACK to try and destroy the menace by MacGyvering a nuclear bomb ("a small one," granted) out of the nuclear power plant. Why Cassidy's Token Scientist doesn't explain that ghosts probably aren't going to be affected by a nuclear blast, but they, as humans, sure as hell are, is one of many, many weak points in the script.

In the end, it's not what matters. This is a buddy-action flick, with Henstridge and Ice Cube as the unlikely buddies, and it's some fun in that respect, although Ice Cube is so babyfaced it's hard to be truly impressed by his tough-guy attitude, and it would have been a whole lot more fun if the two of them had some kind of chemistry. Or, indeed, if Henstridge shared a chemistry with Jason Statham, who has an interesting turn in what would normally be the cute-girl role, fetching and carrying, opening locks, making google-eyes at his Lieutenant. The best part about the whole movie is the gender-reversal aspect, in fact, and it would have been doubly great if the Ice Cube role (James "Desolation" Williams) had been given to a woman as well.

For all the interesting casting (Clea Duvall, Pam Grier, Rodney A. Grant), it never sparks entirely into life. The world itself (apparently the whole thing was filmed in a rock quarry in Mexico) never feels true, and the actors never seem to truly inhabit it. Coupled with the howling miscalculations at the heart of the story, it makes for some rough going. Where it succeeds, it succeeds by the fun we have in spite of all that.

Tuesday, October 27, 2015

halloweenfest triple feature: circus of fear, chocolate, and bonnie and clyde vs dracula

Circus of Fear:(1966. dir: John Llewellyn Moxey) Ah, Carnaby Street! Peglegs and moppy hair and anglophilia. This isn't, it turns out, a horror film so much as a murder mystery concentrated around a travelling circus. The production is a German/English cooperative effort, with a mixed cast of tommies and huns. Christopher Lee is here, playing a badly scarred lion-tamer and wearing a bag over his head for most of the film (but what eyes! and, when the bag comes off, that marvellous face!), and Klaus Kinski, cold and still and positively glittering with danger. It begins with a cracking good, and largely silent, heist of an armoured car on Tower Bridge (or, as they pronounce it, "Tahr-bridge"). From the first shot, a close-up of Kinski projecting a quiet enjoyment of his own inimitable menace, until the first murder-by-circus-knife, it's great fun. It slows up as it moves, giving us circus-folk in-fighting, probably too many tangled back-stories, and a smirking detective who is constantly being offered cups of tea, but it's still a good time.

Chocolate: (2005. dir: Mick Garris) The Masters of Horror series is more miss than hit. The trouble seems to be that the entries are short enough that the "masters" assume they can get away with the shadow of an idea, rather than a fully thought-out script. Chocolate is one of Mick Garris' entries, and it's a particularly wretched offender.

The dialogue is pretty awful, especially once the "love story" starts. The initial idea is not earth-shaking: a lonely man begins, suddenly, continually, and for no reason that is ever made clear to us, having spells during which he experiences the world through the senses of a beautiful stranger. Soon, he knows how to love like a woman, be fucked like a woman, and, since it's a horror film, commit murder like a woman. He tracks the stranger down, convinced he's in love, and it's no spoiler to tell you he winds up with her blood on his hands (and neck, and down his shirt-front), because the framing device is his police interrogation and he confesses as much in his first words.

The only thing it's got going are a few effective visual and aural effects, when he's fading from one "reality" into another. Believe me, it's not enough to make it worthwhile.

And that's too bad, because Henry Thomas deserves better. Watch Dead Birds instead.

Bonnie and Clyde vs Dracula: (2008. dir: Timothy Friend) This was a family project. Practically everyone who worked on it has the last name "Friend", and that doesn't bode well, right? But this one has some mojo to it. Despite a tiny budget, it's got really good lighting, good photography and music, and the two lead actors are engaging. I think this guy spent his whole budget getting an honest-to-god scream-queen to play his Bonnie (Tiffany Shepis). She's good. The only downside of her casting is that when she gets out of the bath you get pulled up out of the movie thinking, "Did women really shave off their pubic hair in the 1920s?" (I googled it. They didn't.) In a production this tiny, there are going to be weak spots, bad performances, etc, and there are. The sound is not great, and one of the characters in particular (the "innocent" sister) is just awful, just a terrible idea with a terrible realization.

On the other hand, there was one plot twist in particular that I didn't see coming, and it's just so brazen, the whole thing, I couldn't help but dig it.

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

halloweenfest evening one: dark was the night

(2015. dir: Jack Heller) It's a familiar and well-loved tale: unnerving and inexplicable tracks in the snow, an ancient beast from Native American legend displaced from its secret home by a logging operation, a small-town sheriff called reluctantly from the hypnotic trance of his own personal demons to an act of heroism which will save his town. In fact, the external and the hero's internal, mirrored "demon" seem to be linked, as if the sheriff's guilt over the death of his young son is somehow catalyzing the outer battle. Stuck in a swamplike ennui made of his own heavy shadow, he rejects the monster as a clever prank, indeed, rejects every plea for help, as from a horse-owner who's lost an animal to the phenomenon, prefering instead to fade into the background and watch as events play themselves out.

One of the movie's roots lies in an old Fortean story known as "the Devil's Footprints". In 1855 in Devon, England, folks woke to a trail of some 100 miles of inexplicable hoofprints in the snow for three nights running. The prints not only defied expectation by being "single file", but by travelling right over haystacks, even rooftops. The maker was playful: sometimes the prints seemed to duck into a small drainpipe and emerge from the other end. Explanations put forward included an unmoored balloon dragging a weight behind it, wood mice, badgers, a very lost kangaroo, hoaxsters, or the devil himself. In this case, it's something more mysterious.

The film's palette is relentlessly blue, mirroring the approaching winter storm. The story is told sparingly and well, the town itself brought to life in easily moving pieces, put forward at a small-town pace. Lukas Haas shines in his down-playing as the big-city deputy, and the townsfolk, the wonderful Nick Damici among them, are believable and low-key. The initial hoofprints are chilling, and the slow reveal of the beast (we do not see it clearly until the end) is remarkably effective as the thing travels like a gargantuan squirrel through treetops. It's an old-fashioned, slow-building suspense, an art-form near-lost, and Heller is to be applauded for championing it.

The downside is that, although well-crafted, the formula is so strictly followed as to become claustrophobic by the end.

Recently I read an interview with Emma Thompson in which she complains that throughout her thirties and forties she turned down hundreds of scripts in which her role could be summed up as begging the hero not to do a very brave thing. Since I read that, I'm astounded to find this "don't-do-the-brave-thing" role absolutely everywhere, and I'm even more agog that I never noticed it before. From Andromache begging Hector not to fight Hercules to Calpurnia begging Caesar to stay away from the forum, it's an ancient and hackneyed trope and you will find it in every third movie you watch, maybe every second one. Bianca Kajlich is lovely here as the sheriff's estranged wife, but she is filling this same role, and by the time he goes off to face his end-battle, taking leave of his son with that moth-chewed, "take-care-of-your-mother-until-I-come-back" chestnut, the dialogue has left any vivacity far behind.

The sheriff gathers the townsfolk together in the church to weather the night of storm and monster, and, within this traditional fortress, the climactic showdown will play out. At this point, it's as if the writer stopped setting the story's course and put it on autopilot for the end, giving us the moments (including the last-minute twist) that we've come to expect. It's too bad. It was almost something extraordinary.

Monday, October 5, 2015

a sorry chris evans triple feature

the Perfect Score: (2004. dir: Brian Robbins) Evans is miscast. It ought to have been someone a shade geekier, maybe a Chris Marquette. He ought to have played instead the love-wounded Matty, opposite Scarlett Johansson, with whom he's proved in six films to have an easy but palpable chemistry. This is an MTV revamp of the Breakfast Club, brainless, witless, and without merit, excepting the few moments of truth the young actors can coax from the piece. Erika Christensen, for example, is the smart girl who learns to tap into her inner slut. She gets the awkward, stuck-inside-her-head part right, but does nothing else particularly well, and the bit on the rooftop where she's finding her passion is forced and uncomfortable.

It doesn't matter. Nothing would have saved it. It's narrated by the Asian stoner dude who's a secret maths genius, and you can imagine how badly that plays: shamelessly for laughs, laughs which never come manifest. The token black guy is a basketball star whom the script treats as ridiculously asexual. It's embarrassing: in the end, the white kids pair off, while the Asian and the black guy don't even enter into the game, although it's obvious that Desmond (Darius Miles) is the character who has the chemistry with Christensen's smart girl. There's something grotesquely 1950s about it.

The other revelation is that Chris Evans doesn't play the straight man well. In his defense, his "comic" foil this time is Matthew Lillard as his older brother, again embarked upon his tired (you can tell even he's tired of it) "hyperactive party 'tard" routine, and that can't be easy to be around. And, to be fair, Cellular came out this same year, in which Evans does very well as straight man in his scenes opposite his scuz-buddy (Eric Christian Olsen), so it may well be a matter of script quality. And, come to think of it, direction, as well: in Cellular, Evans is allowed to be quicker on the draw, which he seems to enjoy, whereas Perfect Score is edited with long reaction shots before and after lines, which does nothing but protract the stupid thing.

If there's a reason to watch it, I can't think of what it is.

London: (2005. dir: Hunter Richards) This guy Richards raided the set of Cellular (Evans, Biel, Statham) and wound up with a much better cast than he deserved for what seems to be a very personal indie projet-du-coeur about the agony of being rich and gorgeous and just wanting to be loved on your own terms, goddamnit, and I'm going to stand in this bathroom doing cocaine until she loves me for the reasons I want her to.

The fact that Richards got Statham, with his super-virile presence, to play the impotent guy was an enormous coup, and Evans and Biel do everything they can, he playing an asshole who just can't quite stop himself being an asshole, she playing a homely gal, -- just kidding!-- the embodiment of All Which Men Desire, and they BOTH JUST WANT TO BE LOVED ON THEIR OWN TERMS, IS THAT SO MUCH TO ASK? Like I say, both actors do what they can.

We spend most of the movie in a luxury bathroom about the size of a Tokyo apartment, half mirrors and half balustrade overlooking the city, doing coke off a Van Gogh casually pulled down off the wall. Mostly the Evans character is avoiding having to confront the woman he obsesses over and wants to dominate (calling his yearning by the name of "love"), the woman who is leaving him for a guy with a 10-1/2 inch cock (seriously, it seems that if the guy had a smaller dick, the loss wouldn't be so traumatic. But this is True Love, mind you).

Sometimes the conversating is more interesting than others. Sometimes we're stuck in an infernal round of flashbacks in which fucking, fighting, and whining are an endless ring in some Sartrean hell.

*SPOILER ALERT*

Puncture: (2011. dir: Adam and Mark Kassen) This is the bleakest lawyer movie you will ever see. It's like the Verdict only without those brilliant, icy spaces, and, significantly, without that miracle pitch in the ninth, the one that sends James Mason's unflappably smooth and malevolent lawyer into a much-cheered moment of stammering. This is Erin Brockovich with six-pack abs instead of cleavage, but instead of a plucky, foul-mouthed gal who won't give up, this guy is a drug-addicted sleazebag who lives his life on the edge of surrender, snorting coke in public johns and getting handjobs from his students. He obsesses over this one unwinnable case for the wrong reasons, possibly because he knows his body is about to give out and this is his last chance for salvation, and in the end, it is suggested, gets himself Silkwooded instead: suicide by waving a red flag in front of Big Business. The trouble is that his last, noble speech is one we don't really buy, because by this time we're familiar with this guy's brand of bullshit, and it seems ridiculous that anyone in power would go to the trouble to take him out because he's such a powerless, sadsack freakshow. After his death, almost as an afterthought, his ex-partner and the client, remotivated by his untimely demise, find their moment of victory, but the way it's presented seems hollow and a little glib.

Evans is good. He has that Paul Newman thing going, that rare, extreme level of likability that allows him to play an utter douchebag and get away with it. After watching this and London side by side, though, I never want to have to watch Chris Evans snort cocaine, ever again. Maybe a nice pot-smoking surfer next time, just to mix it up a little, OK?

Wednesday, September 16, 2015

a bad guy amongst the bad guys: chris evans in the iceman

(2013. dir: Ariel Vroman) A thing few actors can do successfully is to alter their personal rhythm for the length of an entire film. Yeah, you can make a point of talking faster, jumping harder on your cues, or, like Jeremy Irons in Reversal of Fortune, you can slow yourself down just a notch, give yourself a solider center to work from, sort of jerryrig a strength of gravitas. Most of the time quickening your natural pace comes across as caricature (not always a bad thing: think Brad Pitt in Twelve Monkeys). At its most effective, you get the caged explosions of Ralph Fiennes in In Bruges, or, even better, Ben Kingsley in Sexy Beast, this last surely one of the most terrifying performances ever. Slowing one's energy, on the other hand, results in a confined performance (which worked towards Irons' Oscar, that stoical mien allowing the creepiness of his possible guilt to blindside us at the end).

The fact is, you know you're going to get a different tempo if you cast Christopher Walken, Samuel L. Jackson, Al Pacino or Michael Caine. You can pretty much count on it, and you have to, because complementary tempos make for great exchanges. Butch is quick, Sundance is steady. You cast the rapidfire Pesci opposite the steady DeNiro, and sparks fly when Robert Downey's staccato Tony Stark kicks up a bromance with Mark Ruffalo's cautious Bruce Banner. In Bruges works because Colin Farrell is fast and furious, Brendan Gleeson is slow and steady; McDonagh's follow-up 7 Psychopaths suffers because he's cast Farrell in the steady role, playing off the unstoppered stream-of-consciousness that comprises Sam Rockwell's hit-and-miss wit, and Farrell feels hogtied. You can tell it because when he finally gets to play off the (slow and steady) Walken, he brightens up, comes to life. (And, speaking of Walken, remember the classic "Sicilian" scene in True Romance, the one where Dennis Hopper talks his ear off? It works because Hopper is quick, Walken is steady.)

Even when an actor "disguises" himself well, he's not usually doing it through tempo-change. Daniel Day-Lewis is our current shape-shifter laureate, and yet the quickest he ever gets is, what? the punk kid in My Beautiful Laundrette? (I haven't seen a lot of his work, so help me out here.) My point is that even our best actors, even our Streeps, may speak more quickly or slowly, but the natural energy-tempos tend to stay the same.

Now I want you to look at Chris Evans. As Captain America and in other roles (Cellular, Push, Street Kings) he's slow and steady, but he always has a tendency to jump right on a cue. You come away thinking you have a clue into the man himself, that this is the way he presents himself in the world. Then you watch the Losers and the Iceman, and you get a whole different guy. He's quick, he's surefire, he can go forever without a pause, and, particularly as Mr. Freezy in the Iceman, his performance still seems thoughtful and intelligent. This is a smart guy; his mind just works so fast he never has to show you he's thinking about what he's going to say. If you're not looking for Evans in this movie, you won't recognize him. He's disguised himself, yeah, with moppy hair and '70s glasses, but he's also accelerated his tempo so successfully that just don't catch a glimpse of the good Captain, not a single one, and that's no easy accomplishment for a matinee idol of his stature and fame.

As far as the rest of the movie goes, it's Michael Shannon as a mob hitman. You know what to expect, right? Sure, he'll be great, he always is, but you know his coldness by now, his scariness, you think you don't need to see it because you can guess his moves, right? But not so. He's mesmerizing to watch. And I fully guarantee that in the last few minutes, his closing soliloquy, he'll blow you away. He's that good.

Tuesday, September 8, 2015

chris evans when he plays a normal human

It didn't start out to be a Chris Evans thing. I actually started out watching movies with (the uncannily brilliant) Cillian Murphy, and that's how I got to Sunshine. It's the Danny Boyle sci-fi in which the sun is old and tired and mankind is trying to restart it with a nuke to its innards. It underwhelmed me the first time I saw it (not scriptwriter Alex Garland's fault, or the cast's, who are lovely; I think the blame rests entirely with Boyle), but I was fascinated, on returning to it, to find Captain America there in the crew. And not just playing any crew member, but the Shadow-Carrier: the macho flyboy who is determined to save the world even if he has to kill everyone onboard to do it. It interests me that the very quality of earnest guilelessness which he so effortlessly exudes and which makes him uniquely suited to play America's humblest superhero redoubles its strength here, in a role which any other actor would have given an inappropriately black-hatted hue. When crisis strikes, every action this pilot takes is thoughtfully aimed toward seeing the mission accomplished, the sun recharged, and the earth saved. Everyone, himself included, is expendable to reach that end. He's a good guy, a hero, and in the end he gives his life in a particularly difficult and unsung fashion to see it achieved. Somehow, miraculously, Evans never seems villainous, even when he's snarlingly alpha-maling at Murphy's physicist-protag or coldly condemning a shipmate to death by execution. It's a stunningly successful performance in a sadly unsatisfying film.

Evans' career so far is crazily skewed toward the superheroic. Besides the good Captain, he's twice been Johnny Storm, 2009's Push concerns a motley group of mutant-kids with superpowers, and Scott Pilgrim Vs. the World has its own superhero thing going on. Even when he's not superheroing, he's plain heroing, as in Snowpiercer and the Losers, a movie with roots in the comic book world and dealing with an "A-Team" band of military hero types, sort of flawed (but just barely) demi-psuedo-superheroes. (In this one, Evans gets to be funny, and he really is; like Channing Tatum kind of funny-gorgeous that doesn't somehow seem fair to the rest of mankind.)

Of course, Evans looks like a superhero, probably more than any other actor. He is, in fact, so ridiculously handsome, with a body so exactly sculpted to reflect our modern conception of extreme masculine pulchritude, I wouldn't be all that surprised to find out that he didn't really exist at all, that he is just a complex CGI image created by some genius on a computer at Marvel to populate an annoying lacuna in the casting pool. It's his ingenuousness, though, that makes him the true rara avis, and although his talents are often belittled, the frank ease with which he communicates thought and feeling without drawing extra attention to himself is positively refreshing.

And every now and then he plays a normal human.

Cellular: (2004. dir: David R. Ellis) The worst parts of Cellular, an unabashed action B-film from late director/stuntman Ellis, are all in the first two minutes, when Jessica (Kim Basinger) walks her adorable little boy to the school bus. This is the treacly schmaltz setting up the impossibly edenic life (Jessica is a high school science teacher married to a realtor, yet they live in a house the size of Balmoral Castle, complete with swimming pool and serving staff) which is shattered in the third minute by the intrusion of brutal kidnappers. Basinger is terrible in this segment, but she makes up for it in the following couple of hours, excelling at the "terrified-but-strong" mode which propels her through the rest of the film.

The movie is sprung up from a clever notion: trapped in an attic, she manages to repair a broken phone and call a random number, reaching a self-involved but lovable surf-boy (Evans) whom she convinces to run all over town trying to save her family, the trick being that if the call is cut off, it cannot be repeated and he will never find her. Without perfect casting and decent storytelling, it might easily have been too clever for its own good, but the casting really is that perfect, including William H. Macy as the sad-sack cop who ultimately saves the day.

Evans is the pretty-boy loafing around after his ex-girlfriend (Jessica Biel, a small role, and not her best work) on Santa Monica Pier, and he plays it without a stumble, his charm constant without ever tumbling over the edge into the cloying or obnoxious. Complications follow, one upon another, with an easy sweep, carrying us along over the rough patches without too much turbulence. We believe him as the low-key party-boy who is trying to trick his ex into taking him back by faking a social conscience, and we don't mind it because he's obviously doing it out of genuine regard for her. Then we watch him grow up, discover that he does have a conscience, a strong sense of empathy, and a stubborn willingness to make sacrifices for the good of another, even a stranger, and we believe that, too. In short, the story is contrived, but it's well pulled off, and that's all we care about in the end.

One of my favorite things about it is Jason Statham as the chief heavy. Watching this man fight is an unexpected pleasure. His movements are graceful and clean, and evoke that peaceful, exalted feeling you get when you're watching a great dancer, or any true master of his craft at work.

Monday, September 7, 2015

robert patrick double feature: a texas funeral and jayne mansfield's car

a Texas Funeral: (1999. dir: W. Blake Herron) These two movies are extraordinarily well-suited to viewing as a double-feature. They're both family gatherings instigated by the death of a figure of near-legendary proportions, and they're both character-studies leavened, with varying levels of success, with a strong dose of whimsy.

Martin Sheen is Sparta Whit, a larger-than-life, camel-raising, land-rich Texan whose death affects all the life-sized people comprising the next generations of his family. Joanne Whalley is his institutionalized, nymphomaniac daughter, Chris Noth his inscrutable nephew, Olivia D'Abo his frightened niece-in-law. Grace Zabriskie is fantastic as his white-haired, sensuous wife, driven near-mad with lust for what is cagily referred to throughout as "the power of the male Whit ear."

No one has ever been better than Robert Patrick at playing the problematic "man's-man" father who doesn't understand his sensitive son. I've watched him create at least three different versions, and they're none of them carbon copies, all distinctly three-dimensional humans. Compare this one, Zach Whit, a good-hearted, straightforward man who is genuinely bemused by a son who begs for the life of an earthworm about to be used as bait, takes a vow of silence after being told to shut up, and runs away, terrified, when the hunting rifles come out, to the more stoical and wiser Jack Aarons in Bridge to Terabithia, and both of those to his brilliantly courageous turn as the hard-edged Ray Cash in Walk the Line.

Jayne Mansfield's Car: (2012. dir: Billy Bob Thornton) The vibrant, life-loving matriarch of two families, one in Alabama, the other in England, has died and asked to be transported back to the States for burial, bringing the two disparate clans together for the first time. This is about fathers and sons and their ridiculously difficult relations. It's also about war, and how it affects men's opinions of themselves, of one another, and of the world they live in.

Thornton's two best virtues as a director are a fearlessness in taking his own time telling a story and a wonderful regard for those small strangenesses that make us all, even the most "normal" of us, eccentric and individual. His films are more interested in character than story. He takes the time to linger, for example, on a boy at the Jayne Mansfield exhibit, a boy with one line who will not figure again into the story, lets us watch him look at a crude sketch of Mansfield on the wall, then impulsively reach forward and give the picture a peck on the cheek.

This movie is filled with great moments. Here's one of my favorites: Patrick plays the stodgiest of the yank brothers, the only one who didn't see action in war-time. Embittered and driven by his exclusion from the enclave of war heroes around him, he has over-compensated with success in the peace-time world, while his damaged and disillusioned brothers can barely manage to live in it. As the tensions of the family gathering mount and that awful "Thanksgiving" brand of claustrophobia takes its hold, the one that comes of being trapped in a house with too many family members, your secrets and flaws known to all, the alcohol flows in attempt to allay the hideousness and pass the time. After a particularly vulnerable, difficult scene in which the British son (Ray Stevenson, wonderful) at last publicly confronts his father about denigrating his war service because he spent the bulk of it in a prison-camp, Patrick's suburban, middle-class wife breaks into a fit of giggles and suddenly kisses her husband passionately. Surprised, he responds, and they start making out drunkenly on the couch in front of the two older patriarchs. It is a wonderful, human moment, the like of which I've never seen anywhere else, and it may well have been the fuclrum upon which my Robert Patrick film festival first turned.

Wednesday, August 5, 2015

new orleans on film

My Forbidden Past: (1951. dir: Robert Stevenson) New Orleans comes to life in lush and gorgeous black and white, back in the heady days of proud Creole families with skeletons jangling in the closets. You'd be hard pressed to find a more sensuous opening scene: Ava Gardner at her loveliest in slow close-up as she smiles up at Robert Mitchum and is drawn into his silent embrace. (The only one I can think of to beat it for opening-scene sensuousness is John Ford's the Long Voyage Home.) It's melodrama, and the plot bogs down by the end, but Melvyn Douglas is sufficiently roguish in his bad-guy charm to keep things interesting, and Gardner is a masterpiece of fire and ice as the woman scorned and on the lookout for payback. Mitchum doesn't have enough to do, but nobody plays the stalwart outsider better: in this case, a yankee boffin at Tulane.

It's possible that New Orleans never looked so beautiful (and that's saying something) as on All Soul's Eve when Gardner visits a City of the Dead to tryst with her ex and light a candle at the crypt of her scandalous grandmother.

Toys in the Attic: (1963. dir: George Roy Hill) I suppose it's the stuck-outside-of-time quality which makes New Orleans so irresistible in black & white. It invokes that same idea you get sometimes when you're there, if you can ever escape the teeming masses long enough, that if you close your eyes then open them very fast you might find yourself suddenly among ladies in crinoline and gentlemen in shirt-sleeves duelling beneath oak trees and plantation overseers driving wagons filled with bags of cotton to mill. Or that if you stand very still near a boneyard at night (everyone will tell you that going inside at night is utter folly and you'll end up never emerging) you might hear the voices of the city's old gods, still alive and practicing danger and mischief after all these centuries. (When I told my friend Sam I always imagined Venice would be a little like New Orleans, he considered it then said, "The difference is that Venice's gods are asleep.")

This is from a late Lillian Hellman play. As a young girl she lived in New Orleans, and in the time-honored tradition of American playwrights, -- O'Neill, Miller, Inge, ad nauseam,-- although societal influences come to bear, the truest, most stifling danger tends to rise up from the bosom of one's familial unit. To hear these folks tell it, the lucky few who escape its suffocation are so bent and twisted by the time they do it's a wonder that any decent living ever gets done at all.

The play, I'm guessing, sports a seven-character cast, and the movie is slightly opened up, but just a little. We get glimpses of the town: the Cafe du Monde, Jackson Square, the Cathedral, the Preservation Hall. The strip joints and sfumato-painted alleyways at night. Mostly we stay in the sprawling but somehow too-close, much-hated family mansion, probably situated somewhere in the Garden District, where Hellman lived. A pair of spinster sisters (Wendy Hiller and Geraldine Page, both spot-on fabulous) have shelved their own dreams to devote their lives and hard-earned savings to supporting their often absent, well-meaning but wastrel brother (Dean Martin, if not at his best, certainly near to it). When he returns with a kittenish bride (Yvette Mimieux) and a mysterious new fortune, jealousies and fear of change rise up into a mass of destructive force. Hellman is great at this kind of thing. To her credit, she brings the one sister's sublimated lust right out into the open where it can take its true, malevolent dragon-shape, whereas most playwrights would have let it seethe, unspoken, and politely hinted at but unaddressed.

The movie both suffers and triumphs from staying close to the original stage play: there are the first, slightly awkward expositionary scenes, well enough written and acted that we can swallow 'em and move on, but when Hellman gets cooking with fire, she's a fearsome thing to behold, and the build-up to the betrayal is stunning and although you want to look away, it's like a trainwreck coming, and you can't turn your head. There's also a lovely subplot with a rich woman (Gene Tierney, wonderfully underplaying) and her "nigra chauffeur" long-time lover (Frank Silvera).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)