Wednesday, November 25, 2015

halloweenfest triple feature: monsters, absentia, neverlake

Monsters: (2010. dir: Gareth Edwards) Gorgeous movie about two travellers falling in love at the end of the world. It can be read as an allegory concerning U.S.-Mexico border relations, with a melancholy undermessage about how our fear-inspired bellicosities lead to our downfall, but that's mere reduction, and it's far vaster than that. They say it was done on a limited budget, but that's hard to see. The world Edwards has created, with its gas masks, light-being infested jungles, coyotes overcharging for "evacuations", and its alien-invaded "infected zone", feels entirely and fully realized. Really something extraordinary.

Absentia: (2011. dir: Mike Flanagan) Ultra low-budget but inventive and well-executed chiller about two sisters and the horror-film equivalent of the troll who lives beneath the bridge and drags travellers to their doom. Strong, realistic women, an otherworldly threat that is mostly suggested and still effective, and handheld photography that looks clean and doesn't distract from the story. It's a movie made of quiet suggestion, its mystery full-blown but never, as is usual in life, witnessed in its entirety by any single person. Its most unsettling lines are quietly delivered ("You traded with it. I wish you hadn't. It fixates.") and its best exposition given entirely through succinct visuals.

*SPOILER ALERT*

Neverlake: (2013. dir: Riccardo Paoletti) Not straight-out horror, but what you might call Young Adult Horror-Ish. A teenaged girl raised by a grandmother in America is called back to visit her long-estranged father at his villa in Tuscany. Thematically, it fits in with Jessabelle, in that the children (both dead and alive) suffer by and are called upon to rectify the sins of the father. It also falls in with a fairly new and burgeoning tendency toward the examination of the daughter's search for the mother, a new yearning toward the (at this point, still wounded) matriarchal, as witnessed in the Final Girls and the Falling.

The editing and photography far outshine the script here, as does the story itself, which involves a lake into which ancient Etruscans chucked images in order to invoke its healing properties. Toss into the mix a doctor/father who seems to have stepped, ethically, anyway, out of Eyes Without a Face, and there's a very dark story to be told. The fatal weakness of it lies in the dialogue, which hits the ear as if conjured clunkily from the pages of a Young Adult novel, and a pacing which belongs more to the Twilight-esque "don't worry, everything will turn out alright" template than to bona fide horror. In effect, Paoletti wants to tell you his very dark story without taking the risk of scaring you at all.

Monday, November 16, 2015

halloweenfest evening eight: three to avoid

the Thing Below: (2004. dir: Jim Wynorski) Co-opting the plot of Alien and moving it to the middle of the ocean, the Thing Below gives us a ship sent by evil government officials to drag some unknown critter up out of the depths and transport the cargo home. They meet with some weather, the glass jar it's trapped in breaks, yada yada. If you've seen a Wynorski film, you know what to expect. Midway in, Glori-Anne Gilbert appears out of nowhere to do a completely gratuitous, five-minute strip-tease. (I love Glori-Anne Gilbert! You'll remember her from the completely gratuitous skinnydipping scene in Wynorski's equally bad Curse of the Komodo.)

In fact, the striptease is probably the best reason to watch it.

Borgman: (2013. dir: Alex van Warmerdam) Annoying Dutch movie in which quirky transients (possibly the devil and his cohorts) teach some rich folks a lesson by murdering them and their servants, then leading their children away to an unspecified fate. The women in question (the matriarch, the nanny) are ridiculously easy to seduce and obsessive once seduced. Yeah, you're going to tell me it's an allegory, right? That I'm not looking at it in the proper light. That in the original language, it's funny!

Whatever. The only really cool thing is the dogs.

Unholy: (2007. dir: Daryl Goldberg) Adrienne Barbeau swept up in occult governmental research into invisibility, time travel, and mind control? It could be interesting, right? Alas, not really. They never delve much further into these issues beyond the naming of them ("the Unholy Trinity", they're called. Spooky!). There's no true twistiness (alright, there's one good twist, but it's not sufficiently satisfying to absolve the bulk of the crapfest), no images so dark and true they gnaw into your underconscious. There's a conspiracy (who's part of it? everyone? you DON'T SAY!), a bestial Nazi behind the whole thing (yawn), and no interesting theories or ideas come forward. No decent dialogue, either, for that matter.

And who doesn't love Adrienne Barbeau? She deserves better than this.

Thursday, November 12, 2015

halloweenfest evening seven: jessabelle and hands of the ripper

*SPOILER ALERT*

Jessabelle: (2014. dir: Kevin Greutert) Seeking to employ a creeping tension rather than out-and-out scares (and, honestly, the tension never stretches all the way taut), Jessabelle works best in its atmosphere (hoodoo-infused Louisiana bayous) and effective story-telling.

After her life is derailed by an accident, Jessie (Sarah Snook from Predestination) is forced back to her hometown and into her estranged father's crumbling old Southern Gothic house. Immediately haunted by nightmares and spooked by old tarot-reading videotapes left by her dead mother (Joelle Carter, Ava Crowder from Justified, wonderful), she begins, wheelchair-bound but helped along by a childhood sweetheart (Mark Webber), to try and unravel the decaying family secrets.

It's got plot-holes, but they're not fatal: she claims she hasn't seen her father since she was a baby, but when he brings her back to his old family home, he is still living in the tiny backwater where she was raised by her aunt; also, a sudden, unplanned, "secret" adoption staying secret in so small a bayou community is tough to swallow. The visual tropes the haint employs are satisfyingly organic to its plight: the recurring creep of black sludge mirrors the emptying of the underwater coffin, for instance. It's got echoes of that other voodoo-bayou classic, the Skeleton Key, but allows for at least a little feeling of redemption in the end. Although it feels shockingly anathema to our modern sense of fair play, the sins of the father visited upon the child, this kind of vengeance enjoys a long and ongoing tradition in certain circles, and the racial hatred at the heart of the original crime lends an air of the righteous to the avenging furies.

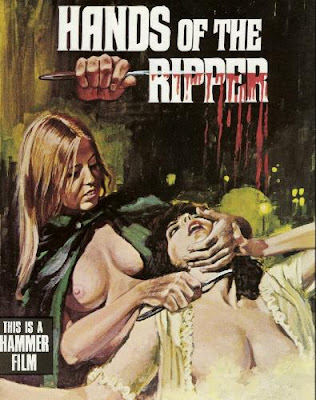

Hands of the Ripper: (1971. dir: Peter Sasdy) Don't be fooled by the poster. This Hammer film, although not without its merit, is far too prim to be emblematized by such Italianate spudoratezza.

A little girl watches Jack the Ripper (who is her father) murder her mother, then he kisses his daughter before he vanishes. Fast forward several years. The orphaned teenager, Anna (Angharad Rees) is being raised (badly) by a fake medium, who uses her to falsify the voices of dead children during her seances. Murderous impulses can apparently be passed down through the DNA, though, because once puberty kicks in, she finds herself falling into deadly fugue states triggered by a combination of flickering lights and kisses.

A well-meaning Freudian (Eric Porter) takes her into his home to try and understand the mechanisms of the homocidal mind. Incredibly, he sticks by her although she commits five or six murders, some in his very house, within the course of two or three days. (It's an interesting Freudian side-issue that so many Victorians of either gender feel compelled to kiss her on so short an acquaintance.)

There's not much more to it than that. There are some nice visuals, as in the climactic scene in St. Paul's, and Jane Merrow brings the needed innocence and light as the sweet, blind fiancee of the doctor's son.

Sunday, November 8, 2015

halloweenfest evening six: trouble at the girls' school

the Falling: (2014. dir: Carol Morley) Inspired by a Fortean phenomenon known as "falling sickness", a hysterical contagion traditionally rising up in girls' schools or convents (see here) this movie has self-conscious pretentions towards Picnic at Hanging Rock. It fails in that direction because it cannot leave its mystery alone, but must turn over every rock, literalize and spell out the urge behind every nuance. Similarly, Maisie Williams' acting style, which can be refreshingly simple and candid in Game of Thrones, is altogether too literal to carry this off, a role which demands subtlety, demands secrets.

Still, a wonderful thing happened about halfway into this film: I realized that I was being shown the story almost exclusively from the feminine point of view. Men, all men, are entirely sidelined here, their opinions and feelings almost wholely discounted as unimportant. It's a wonderful relief, allowing a feeling of exploration, of charting unknown territory. The women are downtrodden, yes, sometimes neurotic, trapped by the actions and opinions of men, but it is only women's reactions to their own hardships which are of interest to this film-maker, and it is a revelatory experience. The sole exception is when she lets us into the brother's head for a piece, and it's a mistake. She does it (I assume) because she thinks it will help make palatable a particularly delicate and pivotal plot-turn if we know that he was enchanted by the doomed girl, that she wasn't just another conquest for him. It doesn't, and it was a mistake to try. I mean, the plot-turn might have been made palatable, but she didn't accomplish it, and some level of purity the film might have had without the boy's intrusion is diluted. In the end, it all seems a bit contrived.

*SPOILER ALERT*

the Moth Diaries: (2011. dir: Mary Harron) If the Falling failed because it was too literal, this one fails because it wants to have its metaphysical cake and still call it psychological. Are the strange goings-on manifestations of a teenaged girl's journey from the darkness of her father's suicide into redemption? Or is there indeed a vampire amongst the budding pubescents?

The director of American Psycho stays perhaps too true to the novel this time. Any power wielded by a first-person narration on the page is often lost once it's imprisoned in flickering light, and the transition doesn't work here. If this is the story of a girl's psychic journey through madness into new life, then why are people dying? Is that all in her head? If people really are dying, then who's killing them? Rebecca herself? The vampire/ghost girl who so eerily mirrors her in circumstance and obsessive nature? In the denouement, when we are given to believe it's all just been a chrysalis stage leading up to Rebecca's fiery release from the bondage of her childhood torment, it feels embarrassingly simplistic. Two deaths, an expulsion, and a terrible fire, all to further one girl's psychological healing? If it worked in the Young Adult novel, it must have been because print allows for an ambiguity which only the best film-makers (like Peter Weir) can conjure, and Harron doesn't come near to making this work.

halloweenfest evening five: dead awake

*SPOILER ALERT*

(2010. dir: Omar Naim) Mangled attempt at a "night-sea journey" movie (Siesta, Jacob's Ladder, the Machinist) so useless that it never even pushes off-shore, just keeps chasing its own tail in the tide-pools, filling time until the contrived sap of its ending.

Dylan (Nick Stahl) works at a funeral parlor in his hometown, having given up on life when his parents were killed in an accident and when, in his grief, he lost his soul-mate (Amy Smart) to another man. He stages his own death (obituary, wake, even tombstone) in a wild attempt to glean whether anyone would care. Or is he really dead, and trapped in a purgatorial dimension? When an unknown woman shows up at his coffin-side, leading him into her dark world, everything turns weird and hallucinatory.

Only not enough so. A true success in this genre melds reality and hallucination so seamlessly that you eventually stop trying to sort them and relax into the march of the story toward the ineluctable, melancholy release which ends it. The ending should feel like a destiny, meted out gently by demiurgic Fates. The motives and conditioning forces buffeting the beleaguered lead should be compelling enough (unacknowledged death, extreme guilt) to warrant the living nightmare. A second viewing should reinforce that the writer knew from the beginning which characters belong to which world: actual, hallucinated, or something in between.

This one makes a mess of it, then throws in the towel completely and stops pretending to be other than hogwash with its forced happy ending. To give the writer his due, it feels like The Evil Studio intervened at the last minute, and that the original, more interesting ending (that his Irish friends are in fact his dead parents) got tossed. The Rose McGowan character, a tweaker with a debt to pay, is even more problematic, and her story doesn't hold up under the barest scrutiny. How could she steal the ring and pawn it under the circumstances? Only if the whole "underworld" she shows him is an "otherworld", pawn shop and mob thugs included, and solid items, like a ring, can traverse the walls between them. Which would have been a more interesting road to travel, right? But someone, possible The Evil Studio, didn't have the grit to follow it through.

I feel bad for Nick Stahl. He deserves better than this.

Sunday, November 1, 2015

halloweenfest evening four: you're next and dark fields

You're Next: (2011. dir: Adam Wingard) Wow. Worst family reunion EVER.

I don't like home invasion films. But, if you have to watch one, if you're inured to the ultraviolence they inevitably afford, this one has some greatness on offer. The best Final Girl ever, for one thing (Sharni Vinson), and there are perfect touches, like the pop CD stuck on endless repeat, those stoical animal masks, and some utterly shameless humor ("You never want to do anything interesting." "I think that's an unfair assessment." "Then fuck me on the bed next to your dead mother.").

The story was written with some care, although some early decisions the characters make are questionable, but isn't that part of the charm of the genre? (Like in the Geico ad: "Let's hide behind the wall of chainsaws!") And, by the end, the kills are far gone into the realm of absurdity. (It's worth it to hear a character ask where his brother is and get the reply, "I killed him with a blender.")

Adam Wingard, who would go on to give us the Guest (if you haven't seen it, for God's sake, man, go and do so) is already sure-handed and unwavering at the helm.

Dark Fields: (2009. dir: Douglas Schulze) There are these great things: Dee Wallace's eerily-swathed husband bearing her aloft in a green room. An enormous, tiled bathroom, like a chapel where the sacrament is performed. The marvellous faces of Cari's parents (Richard Lynch and Paula Ciccone). The top hat. The brightly-colored, shiny raincoats on the little girls. The strange voyage of Mr. Saul. Three separate and well-managed palettes for the three different time periods (1850s, 1950s, and present day). A Native American curse. A shaman bent on vengeance for the white man's genocide. And then, to render it all nearly useless, a script full of dreadful, clunky dialogue which does not come anywhere near to matching the beauty and grace and strangeness of the images.

If it were a silent film, or more nearly silent, say in the style of Valhalla Rising, it might have been magnificent. As it is, it's an undeniable failure, but with moments that will take your breath away.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)